Polygraph technology underwent a history of progression to the modern era, starting in the later 1800s. Of all the people involved with the establishment of the polygraph sciences, Leonard (Leonarde) Keeler had the biggest influence on bringing the modern lie detector machine into existence.

Without Keeler, the polygraph would have remained an obscure device, and it would not have undergone the changes required to make it into the sphere of law enforcement, where it served in the conviction of thousands of dangerous criminals.

So, who was Leonard Keeler, and how did he impact the polygraph sciences? This post shows you the personal and professional history of the man and how he changed the game to gain the moniker “The Father of the Modern Polygraph.”

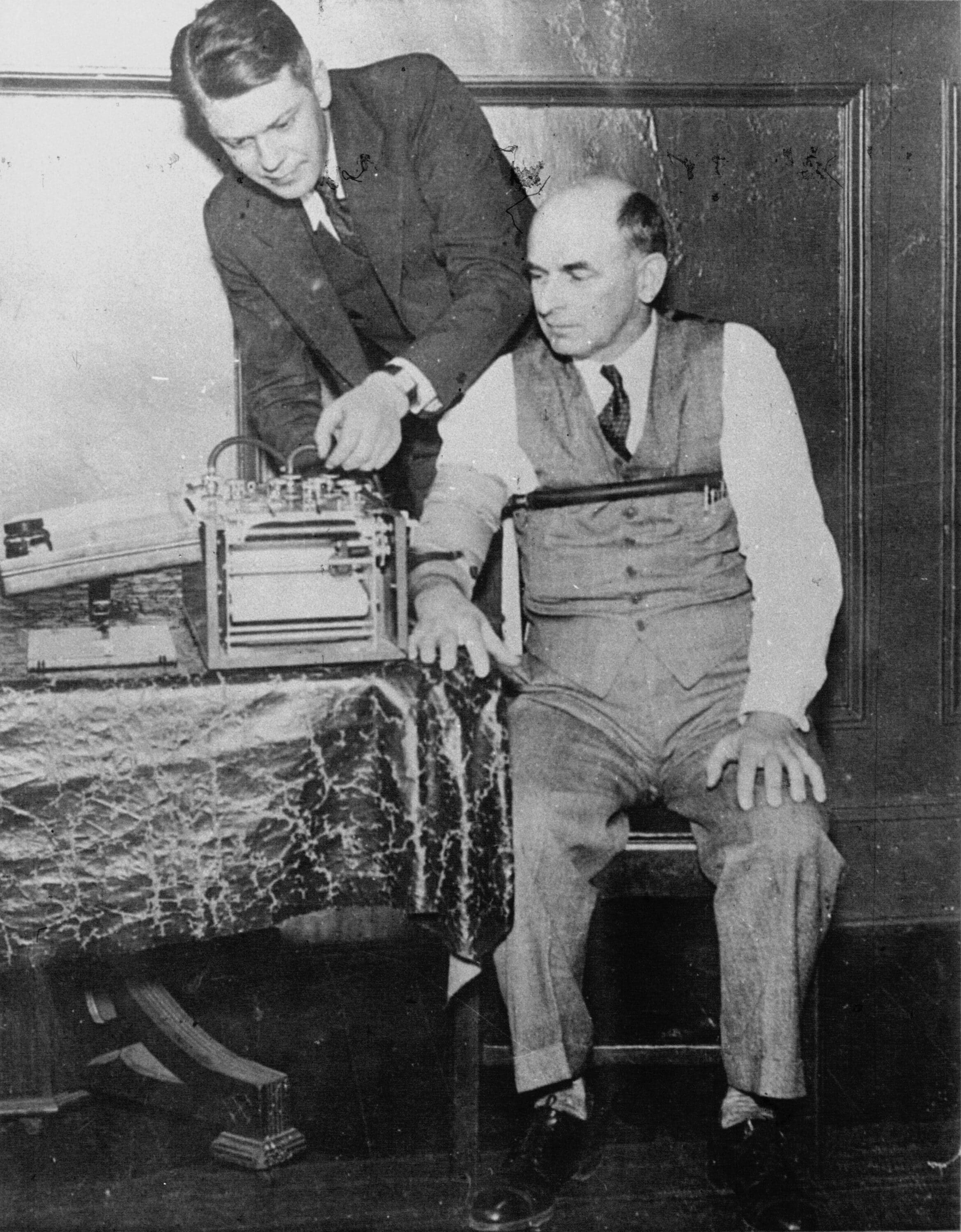

Leonarde Keeler (1903-1949) testing his lie-detector on Dr. Kohler, a former witness for the prosecution at the trial of Bruno Hauptmann.

Who Was Leonarde Keeler?

Leonarde Keeler was born in North Berkeley, California, on October 30, 1903. His father, Charles Keeler, was a naturalist, naming his son after the polymath and inventor Leonardo da Vinci. Leonarde was the co-inventor of the polygraph machine, working closely with John A. Larson during its early development in the 1920s.

Leonarde preferred his friends and associates to call him “Nard,” during his time at Berkeley high school, he had an affection for magic. Keeler found his professional passion after an introduction the John Larson while working at the Berkeley Police Department in the 1920s.

During his high school career, he worked as an intern for the Chief of Police, August Vollmer, at the Berkeley Police Department. He was fascinated by Larson’s “cardio-pneumo psychogram,” which was Larson’s first attempt at making a functional, certified lie detector machine. Keeler worked closely with Larson to produce the first modern polygraph.

After graduating from Berkeley High School, Keeler enrolled at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1923. After a short stint at the university, he transferred to UCLA to follow Vollmer after he accepted a post in Los Angeles as the Chief of Police.

Leonarde Keeler (left) testing his polygraph machine on Marjorie Creighton in presence of August Vollmer during a trial in Chicago in 1932

Leonard Keeler and John Larson

James McKenzie was the first to develop a crude version of the lie detector device in 1902, just a year before Keeler was born. In 1921, John Larson, a medical student from the University of California, progressed the design, inventing the first iteration of the modern polygraph device, which provided much more accurate results than McKensie’s predecessor.

While studying, Larson read the work of William Moulton Marston (1893-1947), a prominent Harvard attorney and psychologist. Marston believed the changes in systolic blood pressure during questioning could indicate if the examinee was acting deceptively during their interrogation by law enforcement.

Marston used a stethoscope and blood pressure cuff to record the examinee’s heart rate and systolic blood pressure response when their heart contracts. It was a laborious and time-intensive process, riddled with inaccuracies.

Still, it was the first time such a device and systematic method recorded a suspect’s deception or truthfulness during interrogations. The machine reached the peak of its popularity between 1916 to 1920 before Larson ventured onto the scene with his own version of the polygraph.

Larson understood the need for a less labor-intensive method of detecting deception, inventing his first device to replace Marston’s. Larson’s polygraph measured the examinee’s blood pressure, pulse rate, and respiratory rate, recording the data on a rotating drum fitted with smoke paper.

Leonarde Keeler progressed the design in 1925, incorporating the use of ink pens to record changes in the examinee’s vital signs instead of smoke paper. The result was a much more efficient machine, with improved accuracy in its results.

Keeler further advanced his design in 1938, adding the metric of measuring galvanic skin resistance to his device. The “Keeler Polygraph” underwent several redevelopments during the next 30 years, with many companies progressing on his designs, even in the wake of Keeler’s death in 1949.

Leonarde Keeler and Katherine Applegate

Leonarde Keeler wasn’t alone in his quest for the truth. Keeler met his love interest in life, Katherine Applegate, when the pair were students at university in 1925. The couple had a romance culminating in their marriage in Chicago in 1930. Katherine underwent training as a forensic investigator, becoming America’s first woman handwriting analyst.

During his college years, Keeler would conduct lie detector tests on his fellow classmates using the early prototypes of his lie detector device. He would ask his test subjects to pick a playing card from a deck and hook up the student to the polygraph device.

During the test, Keeler would ask the examinee to deny picking any cards as he went through each one in the deck. When they crossed the chosen card, they would trigger the lie detector. However, he would often rig the deck to ensure the test’s success. Katherine was the only student to see through his sleight of hand and call him out on it.

The couple became friends, eventually leading to them being aromatically involved with one another. Katherine would go on to found an all-female detective agency in Chicago after the pair moved to the city in 1929.

Eventually, she left Keeler for another man named Rene Dussaq, joining the “WASPS” (Women’s Auxiliary Service Pilots) during World War II. Keeler was heartbroken with the split, leading him down a spiral of depression.

Katherine perished shortly after joining the WASPs. Devastated by her departure and loss, Keeler increased his drinking and smoking habits, resulting in his death in Door County, Wisconsin, in 1949 at the age of 45 after suffering a stroke.

Keeler’s Innovations in Polygraph Technique and Technology

John A. Larson didn’t file a patent for his lie detector device. As a result, Keeler decided to file the patent under his own name. Larson took Keeler on as an apprentice, with the aspiring student taking on the responsibility of improving Larson’s device.

After becoming an employee, Keeler went on to reduce the time needed to set up the polygraph and replaced the need for smoke paper with ink. The “shellacking” required with setting up the smoke paper was no longer required, reducing the prep time.

Keeler would name his version of Larson’s polygraph “the Emotograph.” This device allowed Keeler to file his patent, becoming the first American to hold IP for a polygraph machine in 1925. The patent office approved the filing in 1931, with the application calling the device an “apparatus for recording arterial blood pressure.”

However, Keeler’s first prototype of the emotograph,” was lost in a fire at his residence in 1925. With the need to remanufacture the device, his mentor, August Vollmer, introduced Keeler to William Scherer from the Western Electro Mechanical Company.

Scherer developed a new device incorporating a motor drive, mechanical metal bellows, and “pneumography” attaching to the examinee’s chest. Scherer followed Keeler’s instructions and plan, adding the new tech to the machine and encasing it in a mahogany box, making it suitable for transport.

During the first three months of its release, Keeler and Scherer sold eighty of them to law enforcement agencies in California and across the United States. It was the first mass-produced polygraph machine, with Keeler giving the first demonstration on February 2, 1935.

Keeler used his polygraph machine in Portage, Wisconsin, in a case involving two criminals. After introducing the polygraph results in court, the two were convicted of assault. One of the most successful examples of the early use of Keeler’s polygraph comes from a case in 1937 in Lombard, Illinois. It involved Grace Yvonne Loomis and the murder of her five-year-old son, Roger William Loomis.

Keeler conducted a polygraph exam on Francis Sweeney, In 1938. Francis was the primary suspect in the Cleveland torso murders. Sweeney failed the polygraph exam. However, a lack of evidence in the case led to the dismissal of all charges against him.

Keeler was instrumental in the rise in popularity of modern polygraphy in employment screenings and the rise of polygraph technology in popular culture. He even appeared in the 1948 film, “Call Northside 777” alongside Richard Conte, James Stewart, and Lee J. Cobb, playing the part of himself.

Keeler gifted the original version of the Keeler polygraph to his long-time friend, Leonard Harrelson, as a symbol of their friendship. He also made Harrelson the director of the Keeler institute. Eventually, Leonard Harrelson presented the device to the APHS in 1996 for historical preservation.

Today, the original polygraph, manufactured by the Western Electro Mechanical Company, is in the hands of The American Polygraph Historical Society. The device is nearly 80 years old and looks like a relic. However, it still remains in its original mahogany box,

The device consists of the top panel and kymograph, with the machine’s faceplate devoid of markings, meaning it was likely the prototype since later production models would feature these markings.

Harrelson reports this particular device was used by Keeler in 1944 to examine a constituent of German POW’s at Fort Getty, Rhode Island. The purpose of the polygraph exam was to certify their suitability to earn the role of police officers in post-war Germany in the wake of WWII.

Advancing the Keeler Polygraph – Keeler Model #302

This device carries inscriptions that lend it its historic identity: “KEELER POLYGRAPH / U.S. PAT. NO. 1,788,844 OTHERS PENDING / MODEL 302C / SERIAL NO. 3020331 / ASSOCIATED RESEARCH INCORPORATED / CHICAGO, ILL.” and “ASSOCIATED RESEARCH / Incorporated / CHICAGO / ILL / MODEL NO. 302C / SERIAL NO. 3020331 / MADE IN USA.”

The inventor of this piece, Leonarde Keeler (1903-1949), played a critical role in advancing and popularizing polygraphs, initiating his work in California before continuing in Chicago. Associated Research, Inc., a company founded by James F. Inman (1902-1959) in Chicago in 1936, was involved in repairing and manufacturing electrical instruments.

For more information, one can refer to the patent filed by Leonarde E. Keeler, titled “Apparatus for Recording Arterial Blood Pressure,” U.S. Patent 1,788,484, which was issued on January 13, 1931. Further details about Keeler’s life and his contribution to lie detection technology are documented in a Chicago Tribune article, “Keeler, Famed As Inventor Of Lie Test, Dies” (September 21, 1949), on page 30.

While the Keeler polygraph was groundbreaking in polygraph science, he continued its refinement in the following decades. Many others picked up the mantle after his death, redesigning and developing innovations in the device to improve its accuracy.

The first advancement of his original device was model #301, replacing his second polygraph design, invented in 1925. This was the first polygraph machine built for Keeler by “Associated Research, Inc., a Chicago-based development firm.

Model #301 lasted over two decades before being replaced by model #302 in the 1950s. This device added a third channel, the “psychogalvanometer” to the #301 design. Once again, Associated Research developed the device, adding seven batteries and an AC power source.

The #302 featured a steel casing chromium trim and a wrinkle finish. Its cover attaches to the case using slip hinges, allowing its removal at the testing site. A synchronous motor running at speeds of six or twelve inches per minute powers the chart drive.

The #302 featured four recording pens, with the longer one recording electrodermal variations and the smaller pen monitoring blood pressure readings. The pen recording changes in respiration rate sits above the electrodermal pen. The stimulus marker pen sits at the panel’s top, actuated via a flexible cable attached to the panel’s lower left side.

The sphygmomanometer in the center of the panel actuates the inflation of the blood pressure cuff to optimal levels.

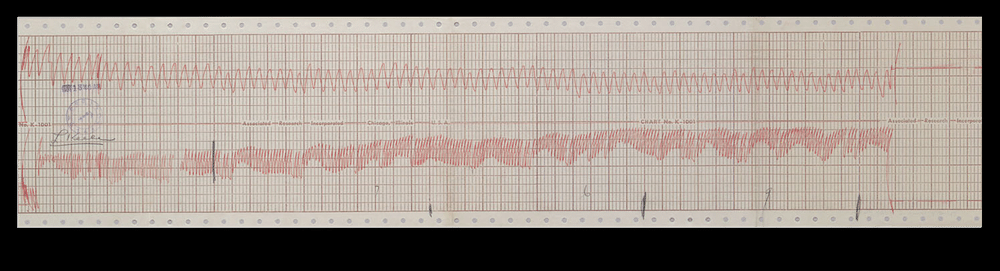

A reading from a Keeler Polygraph machine, 1940. Courtesy of the Leonard Keeler papers, UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library

Further Innovations – The “Keeler Polygraph” Model #6338

There were several redevelopments of model #302 in the coming years. However, the groundbreaking device was model #6338.

Model #6338, manufactured by Associated Research, was the world’s first “Plethysmic Polygraph” system and the first design in the “Pacesetter Series.” This model featured the introduction of a photo/optical plethysmograph, making it a game-changing device in polygraph science.

The Model 6338 was a four-channel device that simultaneously recorded variations in heart rate, blood pressure, blood volume, pulse wave amplitude, blood oxygenation, respiration rate, and electrical skin resistance.

The instrument utilizes electronic and pneumatic monitoring for improved accuracy. Model #6338 featured operation via 115-volt AC current and was a hefty machine weighing 24 pounds. This device included a new inking system and printed circuits, with individually capped ink bottles feeding the pens.

The vent valves in this design featured a positive locking mechanism, preventing leaks. The cardio cuff design, clamp, and pump-bulb assembly remained the same throughout the Pacesetter Series. Advanced Research produced model #6338 in three travel cases to comply with Federal Aviation requirements.

Model #6338 retiled for $2,325.00, remaining in service until the early 1960s.

The Keeler Institute

Leonard moved to Chicago with Katherine in 1929. At the time, the metropolis was known as “Murder City” due to its high crime, homicide rate, and thriving gangsterism. The civic leaders vowed to turn the city’s reputation around, leading them to establish “The Scientific Crime Detection Laboratory” at Northwestern University in 1929.

At the time, it was America’s first formal government institution founded specifically for criminal investigation. Keeler joined the organization, working his way up the chain of command to become head of the crime lab in 1936.

Keeler remained in this position for two years before leaving the lab to open the Keeler Institute in 1938. The Keeler Institute specialized in polygraph sciences, working closely with law enforcement operations and the private sector. Keeler himself worked as a private polygraph consultant for the institute until his passing in 1949.